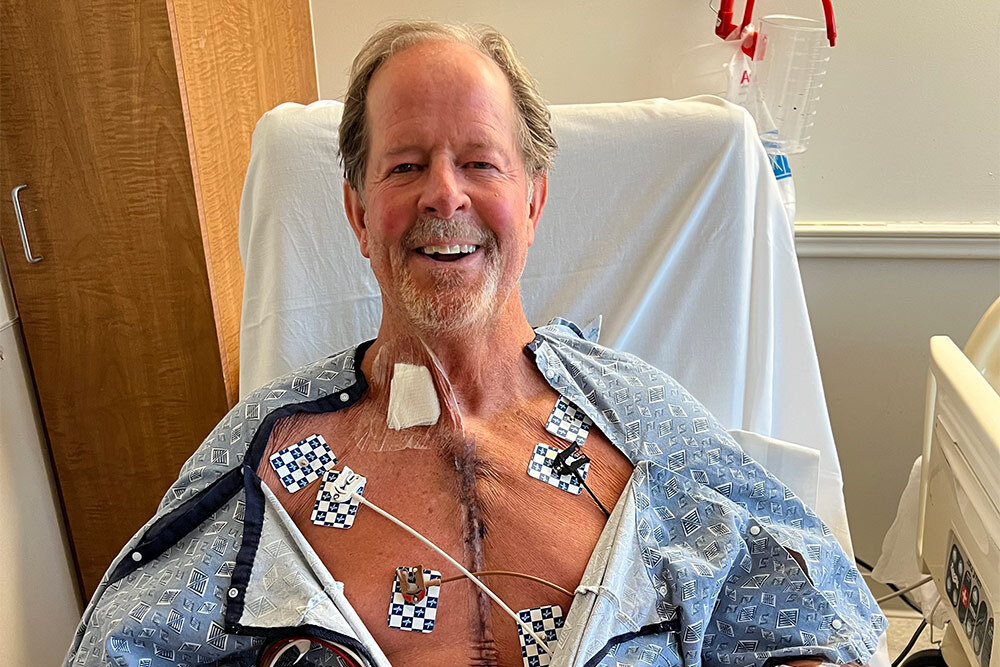

A stroke caused by a rare heart condition prompted Eric Alcorn, a former health care executive, to seek care from a renowned cardiac surgeon Eric once recruited.

When Eric Alcorn helped convince Vaughn Starnes, MD, to join the ranks at the newly-opened USC University Hospital in 1991 (now Keck Hospital of USC), he never dreamed he was recruiting the man who would one day perform the heart procedure that would save his life.

“It was great that when an old friend called for help, he picked up the phone,” says Eric, 65, who worked as an executive at the health system until 2009.

“It’s funny how things come full circle,” says Dr. Starnes, who is now the founding executive director of the USC Cardiac and Vascular Institute, part of Keck Medicine of USC. “I was just glad I could be there and help Eric.”

Recruitment turns into decades-long friendship

As Eric and his colleagues were looking to recruit surgical specialists for the new hospital, Dr. Starnes was identified as a candidate to lead the division of cardiothoracic surgery. At the time, he was the director of Stanford Medicine’s heart-lung transplantation program.

But Dr. Starnes was happy in Palo Alto and wasn’t sure he was interested. He says Eric played a pivotal role in convincing him to take the leap.

“We had many car rides from the Burbank airport to the campus, where we talked about all the great things that were going to happen at this center,” says Dr. Starnes. “Eric made me believe in the dream.”

This marked the beginning of a decades-long friendship. They worked closely together on many projects over the years before Eric moved on to other ventures.

A stroke leads to heart surgery

In February 2023, while Eric was preparing to fly home from a business meeting in Hawaii, he suffered a stroke.

“I lost use of my right hand and my voice,” he says, adding that there had been no warning signs. He was rushed to a local hospital for testing and treatment.

I’ve worked with a lot of surgeons over the years and Dr. Starnes is simply a step apart.

Eric Alcorn, patient, Keck Hospital of USC

“An echocardiogram showed my aortic valve was flopping around like a piece of leather,” Eric says. “It was basically destroyed.”

Immediately, Eric contacted Dr. Starnes’ office.

“He was a friend with a bad problem,” Dr. Starnes says. “I was going to move my schedule and do whatever I needed to make sure I was available for him.”

Rare heart condition caused by a bacterial infection

After receiving images of Eric’s heart, Dr. Starnes confirmed that Eric had endocarditis, a rare heart condition typically caused by a bacterial infection, and which is fatal if left untreated.

“He said it looked like a tiny rainforest was growing on my valve,” Eric says. “He also asked if I’d had dental work recently. I said yes, I’d had a crown put in a few months earlier.”

Endocarditis can be prompted by dental work because bacteria can enter the bloodstream through our mouths. Daily activities like teeth brushing, flossing and chewing food can also lead to an infection.

Despite having no symptoms, Eric was also more at risk for developing endocarditis because he had an abnormal valve caused by a congenital heart defect that was previously undetected.

Dr. Starnes urged him to get to Keck Hospital as soon as possible to address the issue.

“Every beat of my heart was potentially another stroke ready to happen,” Eric says.

In fact, Eric did suffer a second mini-stroke before leaving Hawaii as the diseased valve shed debris into his bloodstream — but he was determined to make it home.

“You want to be in a world-class center with a world-class surgeon to fix a problem like this,” Eric adds.

Eric flew back to California and was admitted to Keck Hospital the next morning. The following day, he underwent surgery.

New aortic valve creates excellent long-term prognosis

During the four-hour surgery, Dr. Starnes replaced Eric’s infected valve with a bovine heart valve, which is made from the tissue of a cow heart. This type of valve lasts for 15 to 20 years before needing replacement.

“Fortunately, it was just the leaflets of Eric’s aortic valve that were infected, not the entire aortic root complex,” Dr. Starnes says. “I could just put in the new valve without needing to rebuild his heart.”

Eric spent a few days recovering at Keck Hospital before he was released. After some follow-up appointments — and a prescription for prophylactic antibiotics to take before any future dental appointments — Eric received an excellent prognosis.

Within four months, he was able to play golf again.

A minor dose of aspirin is the only change to his regular routine, which includes spending time with his wife, five children and eight grandchildren.

“I wasn’t concerned about the procedure itself,” Eric says. “I knew I was in the best hands available. I’ve worked with a lot of surgeons over the years and Dr. Starnes is simply a step apart.”

“I think back to when I was picking him up at the Burbank airport all those years ago,” Eric adds. “I never imagined that one day he would be working on my heart and saving my life.”

Topics